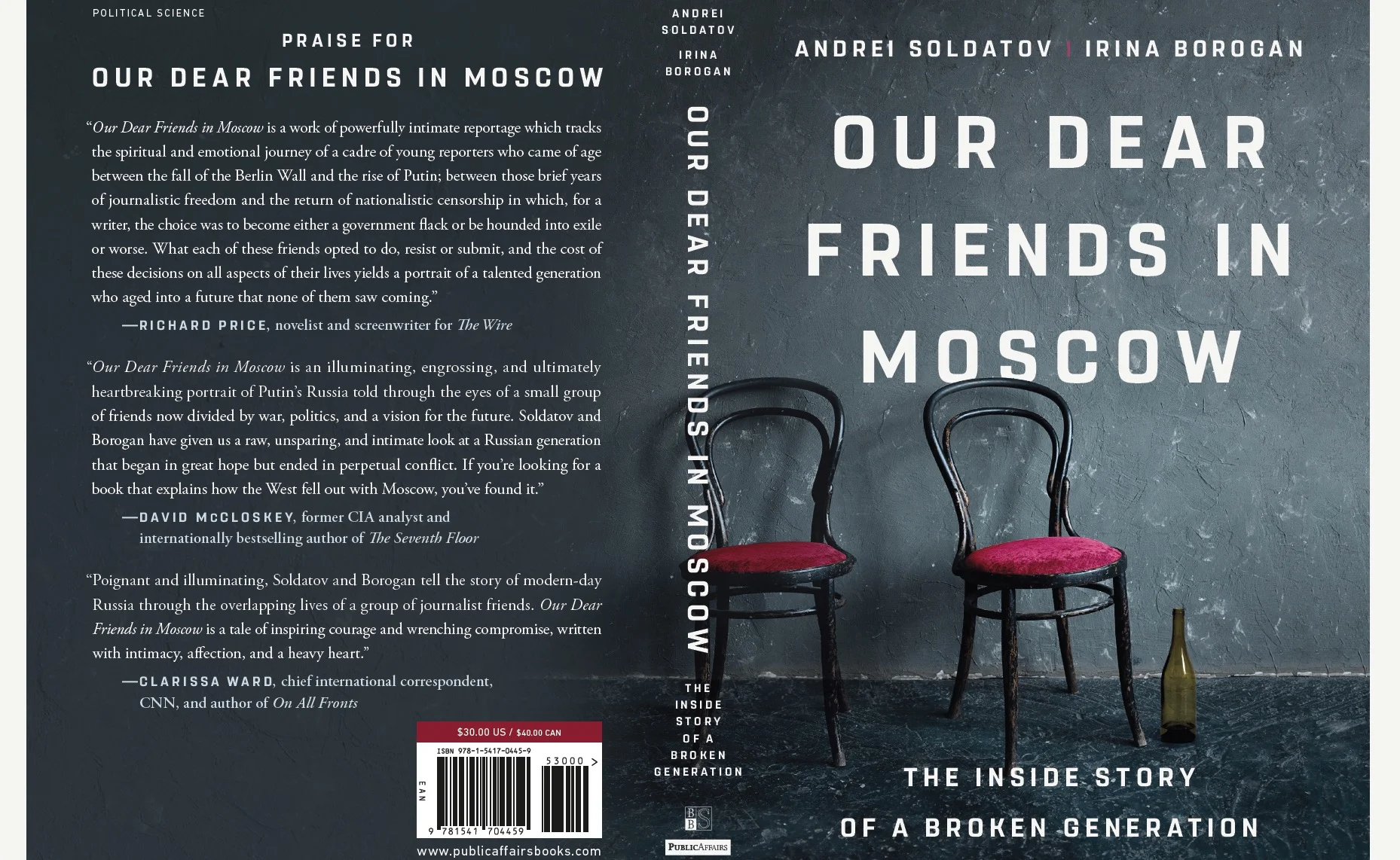

By Andrei Soldatov, Irina Borogan

Russia has always been on the outskirts of Europe, desperate to be inside. The political history of the country is one of constant battle between isolation and modernization through reconnection with the West.

Russia’s way of connecting, isolating, and then reconnecting to the world has often been through war: Peter the Great’s wars, the wars with Napoleon, and World War II, when soldiers returned from battle with a new taste for Western material culture, and some with Western ideas.

The all-out war that started in February 2022 in Ukraine was part of the same pattern. But this time, Russia was fighting against a former part of the Soviet Union, a war in which contact with the West was minimal. There were no British or American soldiers in Russian villages, as there had been German soldiers during World War II.

The result of the war, no matter how it ends on the battlefield, will be Russia’s further isolation. The Western world is now tired of Vladimir Putin, and its sanctions against Russia will entrench the country’s isolation from Western Europe and the United States.

The re-isolation of Russia is not, however, just a consequence of the war in Ukraine. It is, rather, a deliberate strategy intended to reverse a trend that began in 1991, when Russia became more and more globalized. It came closest to the West in around 2011–2012, the moment when Putin decided to reassert his power.

He understood that globalization — through ideas and technologies — was the biggest threat he faced. What we’ve experienced since 2011 is a series of actions and maneuvers intended to detach Russia from the West. After two years of isolation conveniently imposed by COVID-19, Putin made the drastic move of severing the country completely from the West by a full-scale attack on Ukraine.

Our book is the story of Putin’s campaign to wall off Russia from the West, told through a group of friends who were on the front line of the ideological battle over Russia’s future following Putin’s ascent to power. Many of them ended up as key players on the Putin side.

It is a personal story, since they were our friends at a time when we could never have imagined that our lives, our perceptions of truth, and our hopes for our country could diverge so profoundly.

In the spring of 2000, a group of journalists met at Izvestia, a Russian daily newspaper. Putin had just been elected president, and the country was in the middle of the Second Chechen War.

In the years that followed, we kept each other, and our significant others, in sight: Evgeny Krutikov, a deeply traumatized scion of an elite Soviet family whose ties with military intelligence mystified everybody; Sveta Babayeva, a reporter in Putin’s press pool; Petya Akopov, an intellectual with a soft spot for North Korean postage stamps and the North Korean regime; and Zhenya Baranov, a war correspondent with deep ties to Serbia. Later, they were joined by Baranov’s wife Olga Lyubimova, a TV host with close family ties to Nikita Mikhalkov, a film director who had a significant ideological influence on Putin.

By 2022, some of our dear friends in Moscow were serving Putin in one way or another. Meanwhile, we were in London, in exile, separated from our families and wanted by Russian authorities.

What happened? How could we have ended up on such violently opposed sides?

To answer that question, we decided to reconnect with our former friends in Moscow. Thanks to the internet, that was possible even from exile. To our surprise, most of them responded, and some agreed to talk to us.

This book is our attempt to follow this group, and a few other people who would become significant to us, throughout the optimistic first years of the 2000s — a period that included the relative liberalism of Dmitry Medvedev’s brief reign, the annexation of Crimea and the repressions that followed in 2016–2021, and the current attack on Ukraine — to show the journey that Russia has made during these years from a highly globalized and aspirational society to a dismal walled-in fortress.

We needed to reconnect and speak with our friends — the protagonists of the story — for several reasons. The first was obvious: to hear their reasons for what they did. But the second was more challenging: to walk with them through the 20-plus-year journey the country has taken since the early 2000s, and to compare how they — and we — remember what it was like on a personal level at every crucial step along the way.

In a sense, it was like reliving those 25 years all over again. It was not easy, to put it mildly. But in the end, we understood that the crucial choices we all made throughout that journey were probably inevitable, as was our break as friends — our positions had become irreconcilable.

And that meant the rupture the country is going through under Putin was also inevitable.

Our Dear Friends in Moscow, The Inside Story of a Broken Generation by Irina Borogan and Andrei Soldatov is published in the US on June 3 in the US and June 26 in the UK.